JFK Assassination Shenanigans at the Dallas

Texas State

By William Kelly

The first time I ever heard about the State Fairgrounds in Dallas Dallas

Meyers described how he was a salesman from Chicago Chicago Dallas

This particular time, a few weeks before the assassination,

Ruby took him over to the Dallas State Fairgrounds to meet some friends who had

a failing carousel act – a tent where they showed a film called “How Hollywood

Made Movies.”

Meyers said he wrote out a $500 check for Ruby to cash and

share with his friends who ran the enterprise. Two of those involved, Joyce

McDonald and Larry Crafard, went to work for Ruby in the following weeks,

McDonald at the Carousel Club and Crafard as a handyman who became Ruby’s

right-hand man, living at the Carousel Club, doing some of the duties Ruby

usually did, and then helping to manage Ruby’s other club, which never gets as

much attention as the Carousel. Unlike the Carousel, Ruby’s other club didn’t

have the dancers, but featured music instead, usually a rock and roll band.

Crafard also bore a remarkable physical resemblance to Lee

Harvey Oswald, so much so that more than once, it was later alleged that Ruby

and Oswald were seen together, when it later turned out that it was actually

Ruby and Crafard who were together.

Crafard may have also intentionally impersonated Oswald in

one of the many instances where the accused assassin was blatantly and

intentionally impersonated by others, possibly as part of the effort to frame

him.

[Larry Crafard is a living witness]

Then there’s Joyce McDonald. She worked at the Fair and then

worked for Ruby. When Larry Meyers returned to Dallas

Just as a people confused Crafard and Oswald, Ruby employed

two women named McDonald, and they too are often confused. As Ian Griggs notes

in his book “No Case to Answer” ( JFK

Lancer, 2005, p. 224) that, “Betty McDonald (Nancy Jane Mooney) This former

Ruby stripper, who often appears to be confused with others of a similar name,

provided an alias for Darrell Wayne Gardner when he was accused of shooting

Warren Reynolds, a witness close to the murder of Officer J.D. Tippit. This

occurred on 5th February

1964 . Just eight days later, she was arrested in Dallas

According to Griggs (p. 227), then there’s “Joy Dale (Joyce

Lee Witherspoon McDonald, now Joyce Gordon), who is probably the women

recruited by Ruby from the State Fair and who met Larry Meyers. Griggs

describes her as “One of the ‘Five exotics’ who were due to perform on 22 November 1963 , she had worked for

Ruby since August 1963. She is the girl on the left in a series of five

photographs taken in Ruby’s office (Armstrong Exhibit Nos. 5301-A to E). She

was interviewed extensively in the video Jack Ruby on Trial.”

[This may not be the Armstrong Exhibit but Joyce McDonald Gordon is a living witness]

That Ruby would recruit two employees from the Dallas State

Fair was all quite coincidental, and I took it that way until a researcher sent

me some Deep Background on early organized gambling in Dallas Chicago Dallas New Orleans

“At San Antonio On March 6, 1964 , Reverend Wayman Whitney, age 47, 716

College Street , Belton , Texas June 30, 1942 , he left Kelly Air

Force Base, San Antonio , Texas Austin , Texas Dallas Dallas Dallas Dallas

That still didn’t peak my interest in the Dallas State

Fairgrounds too much, but what caught my attention was another reference in Ian

Griggs book “No Case to Answer” (p.

3) in which he describes the operations of the Dallas Police Department’s

Special Services Bureau. Griggs: “This was the first of the specialized

departments. It operated under the command of Captain W. P. (‘Pat”) Gannaway

who was supported by six Lieutenants, 34 regular Detectives, 14 Patrolmen who

were temporarily assigned to the Bureau and four female civilians (one

stenographer an three clerk typists)….Captain Gannaway (at that time known as

‘Mr. Narcotics’) had been in charge of the notorious 1957 undercover operation

and raid that culminated in stripper Candy Barr being arrested for possession

of half and ounce of marijuana. For this offense, she was sentenced to 15 years

imprisonment, actually serving less than three years before being paroled.”

Griggs on The Special Services Bureau: “Initially, I had

some difficulty in working out what the Special Services Bureau actually

did….It was basically a covert surveillance and intelligence-gathering unit

which, as well as the Criminal Intelligence Squad (CIS), included the Vice

Squad and the Narcotics Squad, etc. Its regular officers were plain clothes

detectives…The Warren Commission testimony of Lieutenant Jack Revill (who

became Assistant Chief in 1982) is very revealing…He stated: ‘I am currently in

charge of the criminal intelligence section…Our primary responsibility is to

investigate crimes of an organized nature, subversive activities, racial

matters, labor racketeering, and to do anything that the chief might desire. We

work for the chief of police. I report to a captain who is in charge of the

bureau – Captain Gannaway.’”

Revill was assigned to investigate how Jack Ruby had gained

access to the City Hall basement when he shot Oswald.

Griggs also cites a reference to Phillip H. Melanson’s

article “Dallas

That the DPD SSB, who ran undercover informants, would be

headquartered away from the regular Police Department makes sense, since

undercover informants would not like to be seen around the Police Department

and expose the fact that they were snitches.

Thanks to Robert Howard, who sent this: Dallas Morning News,

page 3 September 28, 1960. “Police to Get Substation at Fair

Park

As Ian Fleming said, “Once is happenstance, twice is

coincidence, but three times is enemy action,” so after my attention was drawn

to the Dallas State Fairground for the fourth time – first by Ruby taking Larry

Meyers there, second by Ruby’s recruitment of two carneys – Crafard and

McDonald, third by the history of gambling at the Fairgrounds and fourth by the

location of the Dallas PD SSU HQ there, I now suspect something interesting is

going on there.

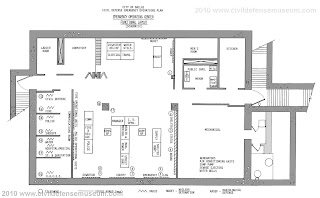

Then the clincher is the fact that the Dallas Civil Defense

Emergency Bunker, an underground nuclear bomb proof cellar with special

communications equipment, was located under the Health and Science

Museum

Was this emergency bunker in use on November 22nd, 1963 ? And if so, did

they tape record all of the emergency radio communications? Russ Baker asks the

same question and notes that Jack Crichton, who worked with some of those DPD

officers in the Pilot Car in the motorcade and assisted in obtaining the

interpreter for Marina Oswald on the day of the assassination, was also in

charge of this shelter.

Russ Baker wrote:

“It was in 1956 that the bayou-bred Crichton started up

his own spy unit, the 488th Military Intelligence Detachment. He

would serve as the intelligence unit’s only commander through November 22, 1963 , continuing

until he retired from the 488th in 1967, at which time he was

awarded the Legion of Merit and cited for ‘exceptionally outstanding

service.”

“Besides his oil work and his spy work, the disarmingly

folksy Crichton wore a third hat. He was an early and central figure in an

important Dallas September 11, 2001 , had a potential

to serve other agendas….”

“On April

1, 1962 , Dallas Dallas Science Museum November 22, 1963 , it was

possible for someone based there to communicate with police and other emergency

services. There is no indication that the Warren Commission or any other

investigative body or even JFK assassination researchers looked into this

facility or the police and Army Intelligence figures associated with it.”

NOTES:

The Office of Civil Defense Mobilization announced Wednesday the approval of a $120,000 emergency underground operating center for the Dallas City-County Civil Defense and Disaster Commission. Under Plans formulated last year, OCDM and

John W. Mayo, commission chairman, said final plans for the

thickly-walled structure will be completed soon and construction is expected to

begin within a year. Largely a communications center it will be tied to state,

regional and national civil defense headquarters. It will contain enough food

and air conditioning to maintain the 20 persons working there for two weeks

without outside supplies. After the center is completed, it will be open to the

public as a display of an operating disaster control office.

Dallas Morning News Staff Photo caption: Officials of the

Dallas City-County Civil Defense Disaster Commission look at a model of an

underground shelter as they announce government approval of a $120,000

underground communications center for Fair

Park Science Museum

Shelter History

The old Dallas Civil Defense Emergency Operations Center (EOC )

is located under the playground in front of the Science

Place Planetarium

Building Fair

Park Dallas

Tx EOC

was to function as a relocation shelter for Dallas EOC lasted from 1960 to

1961 at a cost of $120,000. The City of Dallas EOC

also is equipped with air ventilators containing "anti-blast valves"

which would close to prevent blast pressure from entering the shelter. The air

circulation system was built with a separate air filtration room complete with

a wall of air filters to remove fallout contaminants from the incoming air.

According to a March 27, 1962

Dallas Times Herald article the shelter was officially opened on April 1st, 1962 at 3pm . The shelter is now closed to any public access and is only used

for storage purposes by the Science Place

The old Dallas Civil Defense Emergency Operations Center (

In 2003 some people were

allowed to tour and take photos of the shelter and reported that, “The

Operations Room was the central operations area of the EOC .

This is the largest room in the shelter. During my last trip in 2003 the walls

still had all of the maps and chalk boards that were originally installed when

the shelter was built. The city maps were so old they didn't have neighborhoods

built after the early 60's…”

It appears that they left

many things intact, including the Emergancy Log board. There were still entries written on it from a practice excercise. Some of the entries

are "Naval Air Station Dallas, Carswell Air Force Base, General Dynamics,

Texas Instruments and Power Plant."

Naval Air Station Dallas –

Grand Prarie – from where Z-film was flown to DC by jet

Carswell Air Force Base – Fort Worth 11/22/63 to Dallas

General Dynamics – Major

Ft. Worth defense contractor where Oswald associates worked